Critic's Corner:

Ryan's Hope: Damn Near Perfect, Except...

Afternoon TV Magazine, 1982

by John Genovese

Article Provided By SabrinaRyan’s Hope has amassed more writing Emmys and Writers’ Guild Awards than any other serial. Its creators, Claire Labine and Paul Avila Mayer, richly deserved those honors by painstakingly shaping and overseeing a product that was a unique blend of the new and the traditional—a product that was, and still is, unmistakably their own.

At a mere glance, Ryan’s Hope looks, sounds, feels, and plays much differently from most serials. The acting is full of sparkle and verve. Lines are delivered with as much power and gusto as they would on the Broadway stage, making what few amateurish performances the show has had seem all the more glaringly obvious. The dialogue is alive, fresh, witty and literary, with each individual character given his or her own vocabulary and manner of speaking. Every character—from the pivotal scatterbrain Delia straight on down to the minor non-contract roles—is sharply drawn and recognizable. Most of the boring “soap opera types”—teenaged ingénues, handsome WASP’y doctors with names like Manning and Banning, etc.—are conspicuously absent. And the sets look like the setting, namely New York City, without the haphazard blandness that has passed as Salem or Springfield in recent years.

With these individualistic traits come refreshing treatments of tried-and-true soap situations. Delia could easily have degenerated into the “bitchy daughter-in-law” mold (the Lisa-Rachel-Erica syndrome of the ‘60’s and ‘70’s) only to eventually break away from the core family altogether, but Labine and Mayer constantly produced trump cards which keep Delia somehow connected with the family fold—purchasing the family bar and grill, pursuing another Ryan male, using her Crystal Palace restaurant to impress the Ryans, or seeking bed and board with Maeve are just a few instances. Even better, there is a definite psychological thread which binds Delia to this family—that is, regardless of Delia’s flaky scheming ways, she is still a frightened child who never quite recovered from the childhood loss of her parents. Maeve is the mother figure she craves and adores, the one person from whom she needs constant reassurance. Such fascinating, well-defined character relationships have gone out the window on most of the other serials, which are too busy juggling characters to settle down and write characters.

The Rae-Michael-Kim triangle produced new twists in the mother-daughter triangle formula. All three characters were users out to further their own ends and satisfy their own physical and material lusts, yet all three were, underneath, painfully insecure about themselves. This tainted threesome, in fulfilling their own (and each other’s) neurotic needs, played out some wildly funny situations. Who could forget Kim’s catching pneumonia by hiding barefooted on a cold veranda, while unsuspecting mama Rae was indoors, inundating a frantic Michael with opera records to make him a man of culture? Thank you Claire and Paul, for this classic mixture of Love of Life and I Love Lucy!

The dreaded “syndicate” is another soap staple which Ryan’s Hope handled with finesse and realism. Joe Novak’s family connection with a New York-based branch of the Mafia, and his direct effects on the Ryan family (specifically Jack, Siobhan and the deceased Mary), made for a strong front-burning storyline which was unfortunately interrupted by the recasting of Siobhan and Joe. Had the two roles been recast immediately after Sarah Felder and Richard Muenz left, the plot could have moved along far more efficiently and would not have needed time to re-establish itself upon the arrivals of Ann Gillespie and Roscoe Born in the roles. The worst part of this segment, however, reared its ugly head during the recent Writer’s Strike, when it was revealed that Rose Melina’s estranged daughter Amelia was “Godfather” Alexei Vartova’s adoptive granddaughter. The coincidence was far too contrived to bear, and marred the story’s credibility.

And yet, despite all of its virtues, Ryan’s Hope has a few major story problems which cannot be ignored—problems which may have prevented a fine show from garnering the astronomical ratings of its ABC neighbors.

For one, there has been an irritating choppiness to the storytelling for the past few years. Story directions are too easily altered, and stories too suddenly aborted. Jack’s relationship with the missing Rose, Faith’s friendship with teen alcoholic Craig LeWinter, and the hyped-up murder of Michael Pavel have rated barely a mention over the past several months, at least as of this writing.

With this story unevenness had come an imbalance in character usage. Faith and Bob’s relationship seemed to have developed because neither character had anything to do at the time, then it was forgotten and Bob became just “Delia’s big brother” again. Roger and Seneca, until recently, had degenerated to mere cuckolds for Delia and Kim, respectively. Thankfully, these two male leads are once again prominent as both medical professionals and strong romantic figures.

At this point, there seems to be a concerted effort to involve the entire cast in connecting stories, and the storytelling pace has noticeably picked up. Unfortunately, the writers are once again headed in a precarious direction by integrating movie take-offs in the plot. They already took similar risks with the “King Kong” and “Jaws” elements of two years ago, which were universally criticized as being too esoteric and out of place in daytime serials. This time, we’re into “The French Lieutenant’s Woman” (with the soap-within-a-soap plot) and “Raiders of the Lost Ark” (the Ari-Faith-mortuary shrine story). The “soap” story has been well-spun, in this writer’s opinion, with some wonderfully satiric scenes involving Barbara Wilde’s catty competition with her on-screen nemesis, Pamela Thatcher. Better, it is a story which can be comfortably told within the context of real life, which is—or should be—the stuff of good soaps. The “Raiders” story, on the other hand, appears neither comfortable or realistic.

The majority of soap viewers, in this magazine’s educated opinion, do not care about “curses” or mortuary shrines, any more than they care about escaped gorillas who abduct dizzy blondes—regardless of the writers’ noble intents in the stories. There are more plausible story vehicles which can prove equally exciting, or even more so, than movie concepts which are too “way-out” for the serial norm. This is one instance where the quick wrap-up of a story would be not only acceptable, but advisable, before the ratings are severely damaged.

We sincerely want to see Ryan’s Hope maintain healthy ratings, especially because of its cast. Helen Gallagher and Bernard Barrow are unmatchable as Maeve and Johnny, always pumping warm new life into the roles of the two steadying influences in the show. Randall Edwards’ calculating dizziness as Delia, Nancy Addison Altman’s striking boldness as Jill, Ron Hale’s tough-tender playfulness as Roger, Karen Morris Gowdy’s enchanting softness as Faith, John Gabriel’s no-nonsense earthiness as Seneca, Louise Shaffer’s tragicomic, brittle portrayal of the powerful Rae, and Maureen Garrett’s delightfully quirky interpretation of Elizabeth Jane make for a casting director’s heaven.

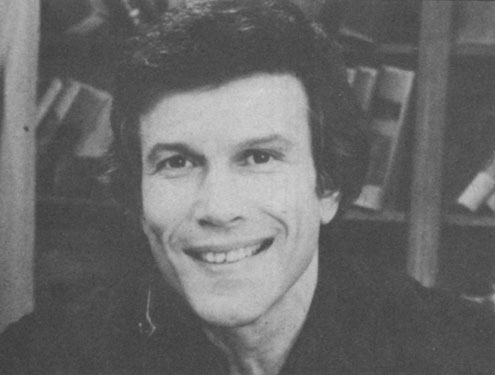

The real star of the proceedings, however, is undoubtedly Mr. Michael Levin as Jack Fenelli. From the show’s very first episode, Levin has imbued the hard-bitten, singleminded reporter character with the sort of explosiveness, passion, and almost frightening intensity that only Michael Levin could give. Jack’s ambivalence toward Joe, his protectiveness of Siobhan, and his great love for mother-in-law Maeve and daughter Ryan could not have been better brought out by any other actor in any medium. Watching Levin at work is watching a master of the craft take total command of his character and his material. This is, by far, an actor’s actor.

Ryan’s Hope is also a leader in technical achievements. Sy Tomashoff, whose sets previously graced Dark Shadows and One Life to Live, has created a beautiful world of smartly detailed interiors on this show. The lighting is carefully done—the sun actually streams through office windows on this show, and this is a curiously rare achievement in the soaps of today. Lela Swift and Jerry Evans’s direction is brisk and varied, and never static. Actors are allowed to move and emote freely, not made to stand like sticks for half a scene. This fluid style perfectly complements Labine and Mayer’s dialogue, which, simply put, rates among the best on television.

In short, Ryan’s Hope is a shining leader in the world of daytime serials. Now if the writers would only channel their energies solely along realistic, human avenues, rather than attempting risky tangents, Ryan’s Hope could become what it once was—and that was damned near perfect.

The RH cast got decked out for an Egyptian

costume ball. Unfortunately, such antics

sometimes stretch the viewer's imagination.

A soap is only as good as

its actors, and in Michael

Levin (Jack Fenelli) Ryan's

Hope has a true gem.